Pastoral care in the aftermath of violence became part of my vocation as a Presbyterian minister in the late 1970s. This was a time when women were beginning to talk openly about sexual violence. I was fortunate to receive compassionate pastoral care at a Jesuit retreat center when memories of my own childhood experience of sexual assault triggered a spiritual crisis.

I was on a silent retreat, away from my infant son for the first time. My spiritual director helped me talk about emergent fears that my son could experience violence, and anger towards God that violence could happen to children.

Traumatic events can be likened to earthquakes that sometimes open up crevasses deep down into those core beliefs, values, and ways of coping that formed us as children. Spiritual and pastoral care can help people identify and explore these embedded theologies that surface in trauma.

This transformative experience shaped my ministry in a number of ways.

At a personal level, I embarked on a long process of liberating spiritual integration that has incorporated my experiences of violence into my spiritual, physical, relational, and vocational growth.

Much of my current research, writing, and teaching focuses on what makes pastoral and spiritual care distinctive form other kinds of care. Theology plays an important role in the unique ways that pastoral care can help trauma survivors.

Spiritual and Theological Dimensions of Trauma

Trauma is the bio-psycho-spiritual response to overwhelming life events. The more life- and self-threatening the traumatic stressor, the greater the likelihood of trauma for individuals as well as for families and communities.

Traumatic events can be likened to earthquakes that sometimes open up crevasses deep down into those core beliefs, values, and ways of coping that formed us as children. Spiritual and pastoral care can help people identify and explore these embedded theologies that surface in trauma.

Embedded theology consists of beliefs and values instilled throughout childhood, which exert an unconscious influence and surface under stress. Embedded theologies are those pre-critical and often unexamined beliefs and practices that have become a habitual part of one’s worldview and practices. People may not even be aware of their embedded theology until they experience an existential crisis or de-centering experience that disrupts their world, pushing deep layers of sometimes unconscious beliefs, values, and practices to the surface.

Such moments provide opportunities to excavate these beliefs, values, and habitual ways of coping, and decide whether such embedded theologies are still relevant and meaningful, especially in terms of helping people connect with a sense of the sacred and make sense of what is happening.

This process of examining embedded theology involves deliberative theology, which Stone and Duke describe as “the understanding of faith that emerges from a process of carefully reflecting upon embedded theological convictions.”[1] Whereas embedded theologies use first-order, often pre-critical expressions of religious experiences, deliberative theology draws upon informal and formal theological education to use second-order religious language to interpret and assess embedded theologies.

Pastoral and spiritual caregivers learn second-order ways of reflecting on beliefs and values through their theological education. Just as health professionals draw upon the health sciences and clinical training to identify, assess, and explore psychological responses to trauma, so, too, spiritual and pastoral caregivers are responsible for exploring, assessing, and helping trauma survivors create religious meanings and spiritual practices that are life-giving for them.

It is challenging for theologically educated caregivers to draw explicitly upon their theological education in the practice of care. Biblical, historical, systematic, and comparative theological studies are highly specialized conversation partners that may not seem directly relevant in spiritual care conversations with trauma survivors.

One’s own beliefs and practices are more immediately meaningful than abstract theologies.

It is also easier to default to one’s own religious tradition than to engage what is different and even foreign about another’s worldview, beliefs, and spiritual practices. Comparative studies of religion are especially important conversation partners for spiritual care outside of one’s own community of faith.

What roles do these theological and comparative conversation partners play in spiritually-integrated trauma care? Theological reflexivity is an interdisciplinary way of integrating theological studies and psychological studies in the practice of trauma care.

The Role of Theological Reflexivity in Trauma Care

Theologically reflexive practitioners engage in conversations that critically assess how their own formative childhood relationships interact with social systems to shape their childhood embedded theologies and adult deliberative theologies.

The process of theological reflexivity begins at this personal level in conversations that hold us responsible for identifying embedded theologies formed in childhood that still exert an influence which may be life-giving and life-limiting for us and/or others. Theological education, especially the kind of experiential education available through spiritually oriented clinical internships and clinical pastoral education, equips pastoral caregivers to think critically about these childhood theologies and whether they are still relevant and life-giving.

Another level of theological reflexivity involves connecting one’s personally meaningful childhood and adult theologies with public theologies that have withstood the test of time.

Theological reflexivity provides a way to integrate one’s theological education into one’s own formation as a caregivers and into care for trauma survivors that identifies, assesses, and respects the unique ways they make spiritual sense of and cope with trauma.

The Process of Change in Theologically Grounded Trauma Care

Theologically grounded trauma care, as I have described it, is based on a theological theory of change. What changes for trauma survivors in theologically ground trauma care?

I describe change in terms of one’s lived theology.

Change occurs emotionally and physically as trauma survivors explore the lived theology constellated by intense trauma-related emotions like fear, anger, guilt, and shame.

In summary, change happens when pastoral relationships help people integrate and embody spiritual practices that foster goodness and compassion with beliefs and values complex enough to account for suffering—one’s own and the world’s.

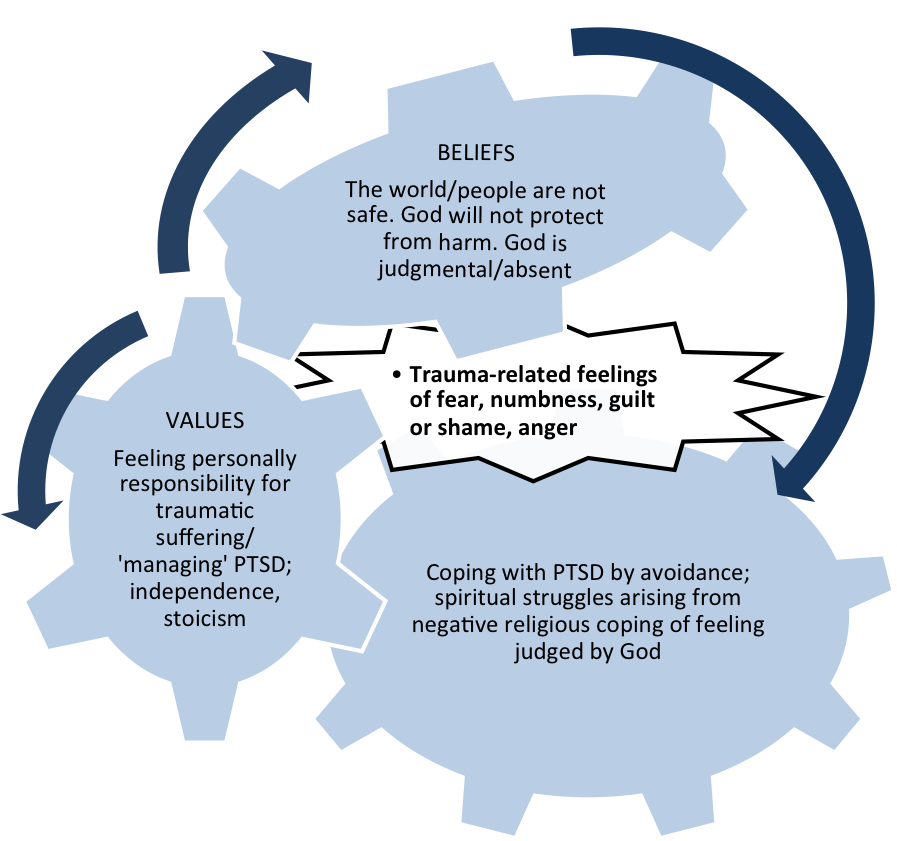

Spiritual practices provide unique resources for trauma survivors. Such practices can counteract the life-limiting theology that trauma may have generated or reinforced. In the following diagram I have represented how a life-limiting theology of values, beliefs, and practices might be energized by trauma-related emotions.

This lived theology might be reinforced by an implicit collective moral theology that makes a woman responsible for managing post-traumatic symptoms and may even make her feel responsible for traumatic experiences and/or how she responded.

For example, a woman experiencing date rape may feel responsible for being vulnerable because of her alcohol use, or perhaps because she felt she did not monitor a seemingly safe context that became dangerous. Religious injunctions against consensual sexual contact outside of marriage could be mistakenly used to blame herself for nonconsensual sexual contact. In the process she may confuse consensual and coercive sexual contact.[2]

The possibility of pregnancy or sexually-transmitted disease might be construed as ways God could punish and publicly humiliate her if she needs to seek medical attention. Without any explicitly religious education about sexual violence, she might assume that her community of faith would shun her if she were to disclose what happened.[3]

This life-limiting theology contains many spiritual “sticking-points”—conflicts between pre-trauma beliefs/values and trauma-related doubts and questions, like “How could a loving God allow this to happen to me?”[4]

In this example transitory religious and spiritual struggles can easily generate a subliminal theology of trauma. Those who experience trauma-related chronic religious struggle use negative religious coping that involves:

(1) Believing in and experiencing God (or some transcendent order) as punitive and abandoning,

(2) Questioning God’s love/humanity’s goodness, and

(3) Being discontented with their religious communities.[5]

Ongoing spiritual struggles and negative coping are associated with increased psychological and spiritual distress.

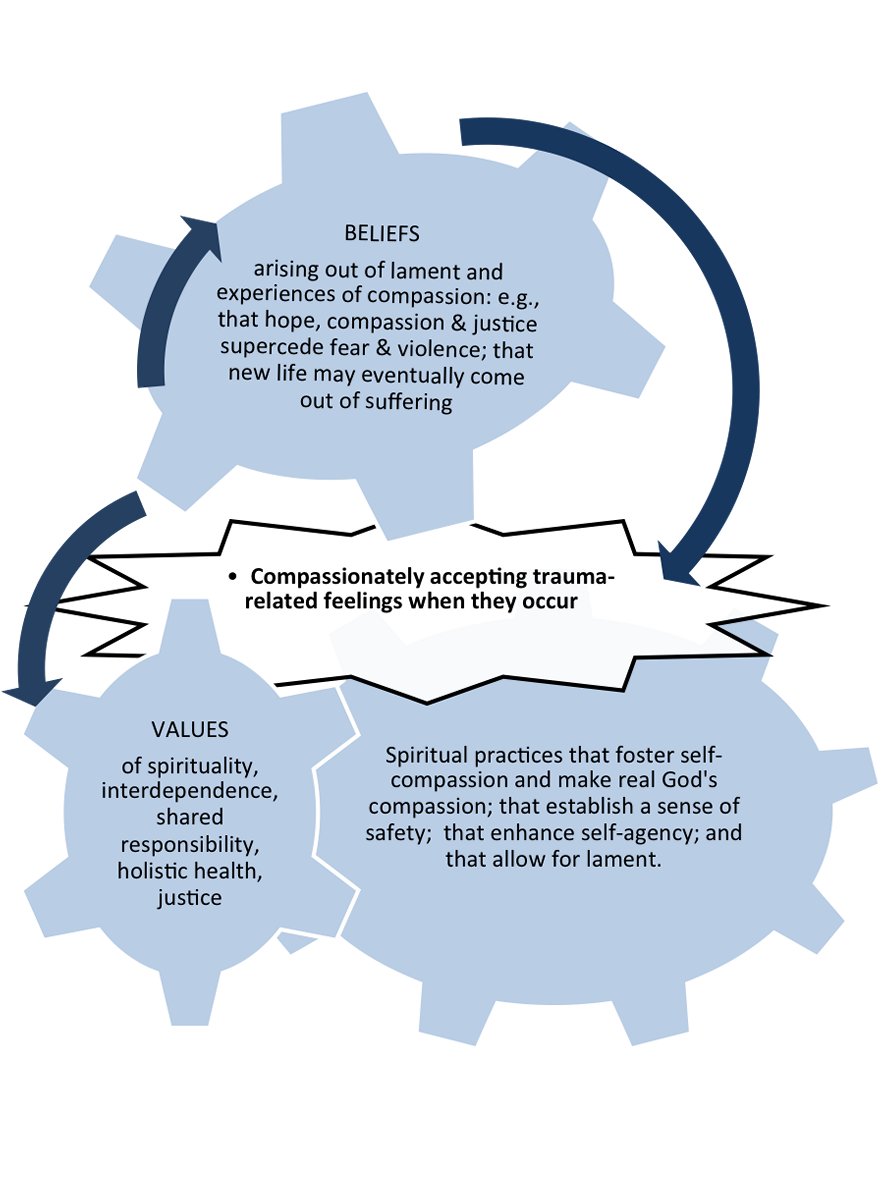

On the other hand, survivors may be able to conserve life-giving practices and beliefs that connect them with God/goodness/support systems. Extensive research demonstrates that positive religious coping decreases psychological and spiritual distress (e.g., anxiety, depression) and increases posttraumatic psychological and spiritual growth, fostering spiritual integration.[6]

What might this kind of life-giving lived theology look like?

A life-giving theology like this can help care seekers resist violence and compassionately accept the traumatic aftermath of violence in whatever ways possible.[7]

Life-giving theologies of traumatic suffering must be capable of ambiguity and complexity.[8]

Theologies of ambiguity hold perpetrators accountable while taking into account the ways persons and families easily become caught in systems in which power is abused, within cultures that often turn a blind eye to or condone violence. The more caregivers and care seekers can learn to integrate life-giving theologies into their everyday lives, the more they will be able to construct religious meanings and spiritual practices that enact justice in their personal, family, communal, and cultural lives.[9]

References