Never talk about politics and religion in polite company, they say. The polite can turn impolite on a dime. Good people are deeply divided by politics and religion—but why?

Jonathan Haidt has an answer. He believes that moral psychology can contribute to our capacity to understand one another, to empathize, and to improve at working together for the good of the whole. I suspect that those who take the time to work through Haidt’s book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, will come away feeling a little more positive about the prospects of discussing our differences and—at the very least—gaining understanding of the values and concerns of those on opposite ends of the religious and political spectrum.

Emotion, Intuition, and Morality: New Cognitive Tools for Creating Empathy

What makes human beings moral? What is the relation between emotion, intuition, and morality? Are moral values products of reason (rational reflection) or of experimentation and socialization? Is morality innate, biological, and genetic, or socially constructed (or something in between)? Are there any moral principles, values, or intuitions that hold steady across cultures (i.e. that can be said to be universal)?

“To better grasp the elusiveness of morality and religion, we need the empirical contribution of the psychological sciences.”

The Righteous Mind addresses these questions—and more besides—but the book also functions as a kind of “state of the union” of moral psychology, as well as a presentation of the groundbreaking research of Haidt and his partners. Haidt narrates his own empirical research, which has played a significant role in the larger conversation about moral psychology. He lays out for us his own research process, including trials and errors, Eureka moments, and collaborative interactions with other researchers and scholars. We get a fascinating look at the way psychological science works today—in its strengths and capacities, as well as its challenges and limitations.

But, most importantly, Haidt offers readers new cognitive tools for increasing empathy with those with whom they disagree—whether theologically, politically, ethically, or religiously (or any sort of conflict, really). His argument progresses in several important preliminary steps.

Who’s Guiding Who?: Intuition and Reasoning

He shows us that morality is neither the result of rational reflection (a learned exercise in determining values like fairness, justice, or prevention of harm) nor merely of innate, inherited assumptions. Haidt gives us the “first rule of moral psychology”: “Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second” (367). Human morality is largely the result of internal predispositions, which Haidt calls “intuitions.” These intuitions predict which way we lean on various issues, questions, or decisions. The rational mind—which the Greek philosophers so valorized and even idolized—has far less control over our moral frameworks than we might think. Intuition is much more basic and determinative than reasoning.

Riding the Moral Elephant: Rationality and Raw Human Experience

Haidt provides the helpful metaphor of the rider and the elephant. The rider is the conscious mind with its rational functions and volitional power. But the elephant is everything else: all the internal presuppositions, genetic inclinations, subconscious motives, and layers upon layers of uninterrogated, raw experience. Needless to say, the elephant is bigger (more powerful) than the rider.

As the rider responding to the elephant, our reasoning process has become well adjusted to the seemingly always-urgent task of justifying our deeper, always latent moral intuitions. Using another analogy, Haidt suggests that human minds are more comparable to lawyers and public relations consultants than they are to scientists who “objectively” seek the truth, whatever the implications of the conclusion. Our minds are well-adapted to providing post hoc justifications or explanations for the moral convictions, “intuitions” that we already possess.

“We are emotional actors! We are highly intuitive beings who act first, and justify later. Our beliefs, convictions, and values are far less “rational” than we imagine.”

This seems counter-intuitive because we have grand visions of ourselves (and our brains are very good at perpetuating these visions!) as rational actors who make measured arguments and have thought carefully about our political affiliations, our moral convictions, and our religious beliefs.

But this is just not the way it actually works.

Haidt provides example after example of empirical research findings in moral psychology that demonstrate the intricate relationship between intuition and reasoning, between moral and conventional reasoning, between emotion and justification. The bottom line is we are emotional actors who act (or respond) first from intuition, and only after the fact of our response do we work overtime to procure rational justification.

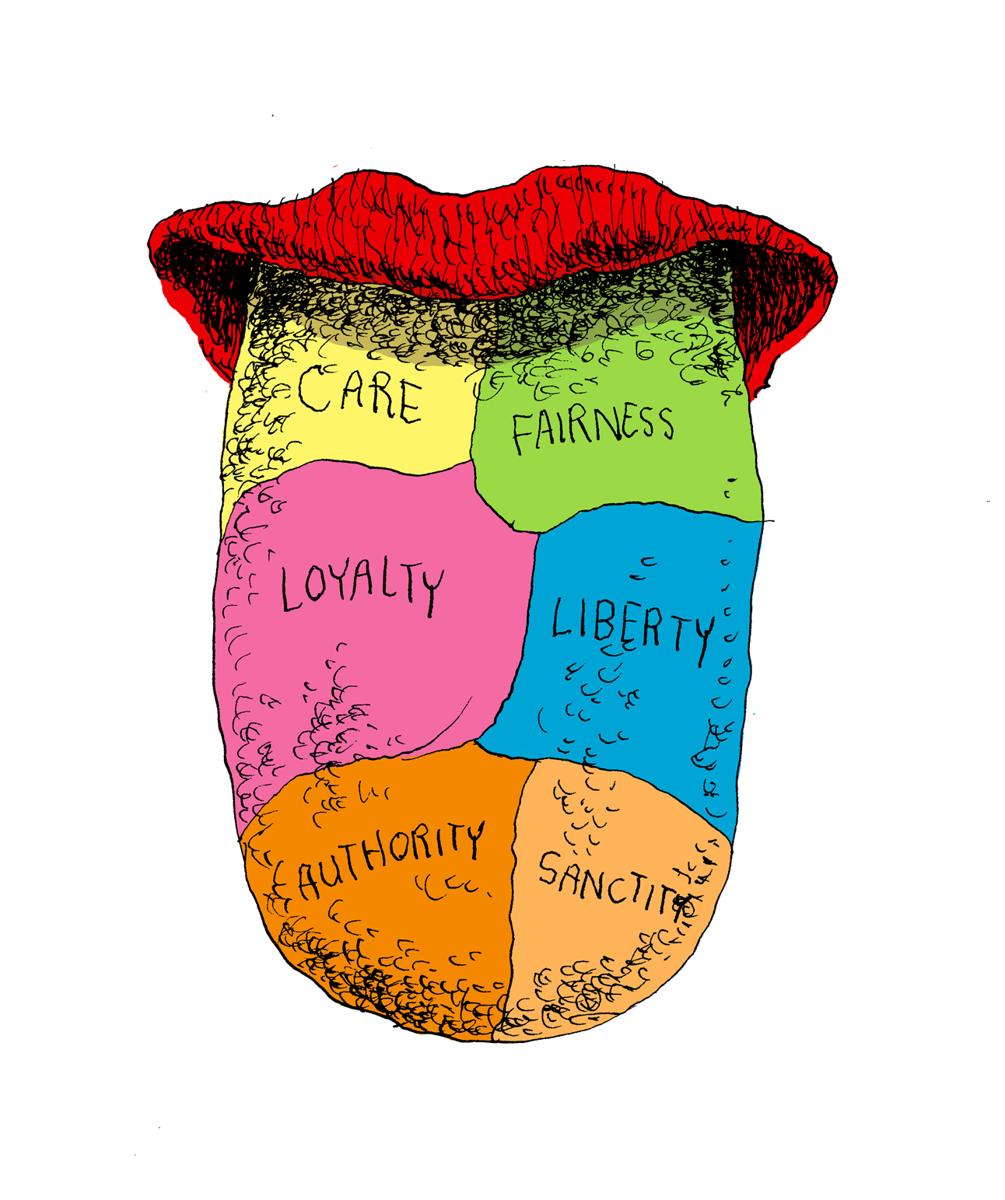

Our Moral Tastes: The Six Foundations of Human Morality

Haidt’s research suggests that human morality can be categorized roughly into six moral foundations, which he likens to “taste receptors” on the human tongue. Each of us responds differently to or is pulled more strongly by some of these receptors than by others. The moral impulses and values beneath major political affiliations can be described with reference to these six foundations.

The foundations are named by what you might call a “dialectic of value,” where each foundation has both positive and negative sides. They include:

(1) Care / Harm

(2) Fairness / Cheating

(3) Liberty / Oppression

(4) Loyalty / Betrayal

(5) Authority / Subversion

(6) Sanctity / Degradation

Moral Foundations Theory At-A-Glance, or, The Six Foundations of Human Morality as Suggested by Social Psychologists.

#1

Care / Harm

#2

Fairness / Cheating

#3

Liberty / Oppression

#4

Loyalty / Betrayal

#5

Authority / Subversion

#6

Sanctity / Degradation

Some of us are predisposed more toward some of the foundations than toward others. We might be more “care/harm” oriented—that is, protecting others matters a great deal. Others might be more “authority/subversion” oriented—where respect is a key value. Still others are inclined toward “sanctity/degradation”—purity being a central factor here.

Some of us are more balanced across the foundations, while others are more intensely inclined toward one or more. As we find ourselves located in or drawn toward particular ideological groups (political or religious), those foundations become more hardened because our identities and our values become more entrenched by our support for the group.

Why Is It So Hard to Have Peaceful Dialogue?

Haidt’s work—along with other moral psychological research over the past several decades—shows us why it can be so difficult to have peaceful, “rational” dialogues about contentious issues. We are emotional actors! We are highly intuitive beings who act first, and justify later. Our beliefs, convictions, and values are far less “rational” than we imagine. We are guided by our intuitions and committed to ideological groups to which we belong. This all creates clear lines of separation and the difficulty of rethinking our views, beliefs, values, and commitments.

“Empathy goes a long way toward lessening the burden of hate or anger that many of us carry with us as we interact with the political or ideological or religious ‘other.'”

Once we understand the situation, however, we are in a far better place to deal with it (and with each other). The main key here is understanding the empirical situation. The fact that our morality is intuitive, and that moral reasoning is deeply emotional and intertwined with our very sense of self, goes a very long way toward empathizing with others who occupy different positions.

Why? How Psychology Can Explain Human Morality

Why do libertarians so highly value individual rights and protections from government influence? Why are Republicans so critical of “government handouts”? Why do liberal Democrats care so much about protecting the poor, vulnerable, and disenfranchised that they would levy big government programs on their behalf? Why do conservative Christians resist gay marriage on the basis of an assumed “biblical” definition of marriage? What is sacred? And why? And for whom?

As a theologian, I am drawn to Haidt’s contribution because it opens up a new way of thinking about ethics and morality. I teach Christian Ethics, and though we invariably present the major “theories” of ethics (utilitarianism, deontology, etc.), we do not often engage the psychology of morality—the emotional, intuitive, psychological underbelly of morality and its various expressions. To better grasp the elusiveness of morality and religion, we need the empirical contribution of the psychological sciences. It also helps us retain a more epistemologically realist and humble approach to our theological reflections.

Binding and Blinding: The Power of Groups, Tribes, and Moral Impulse

Morality—and religion—binds people to each other in groups, or tribes. This moral binding has very positive and constructive effects, both on the group itself and (very often, though not always) on people around the group. But the group binding effect of morality also has a blinding effect, and this is its darker side. We need to work hard at protecting ourselves (and each other) from the blinding impact of our moral impulses. To do this, we need to better understand not just the moral, political, and religious other, but ourselves, too. Haidt writes, in his conclusion:

We may spend most of our waking hours advancing our own interests, but we all have the capacity to transcend self-interest and become simply a part of a whole. It’s not just a capacity, it’s the portal to many of life’s most cherished experiences (370).

Empathy goes a long way toward lessening the burden of hate or anger that many of us carry with us as we interact with the political or ideological or religious “other.” We are certain we are right and they are wrong. We don’t often stop to consider what is motivating others—or even ourselves. But we must do just that. In fact, the very possibility for genuine, positive dialogue may depend on it. Haidt’s final suggestion makes a lot of sense: “We’re all stuck here for a while, so let’s try to work it out.”