Massaging the Message

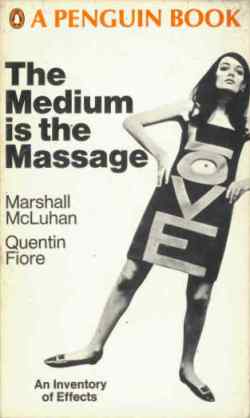

When the esteemed academic and writer Marshall McLuhan got the first look at the cover of his new book, just back from the typesetter, a glaring typo stared back.

For almost any other writer—especially one with such an in-depth understanding of the power of large words printed on a book cover—this would have been a minor catastrophe. But according to Dr. Eric McLuhan (an overseer of the McLuhan estate), his father had a different reaction when seeing that the title of his new work read “The Medium Is the Massage” instead of “The Medium Is the Message”: “ “Leave it alone! It’s great, and right on target!” he reportedly said.

Considering that in this context, the word massage pretty much makes zero sense, this was a surprising reaction. But the happy accident underscored the point he was trying to make better than a perfect title ever could.

The book—which is part visual experiment, part heady philosophical essay, part randomness (some of the pages are completely blank or are written backwards)—became a massive hit when it was released in 1967, and has gone on to be a prophetic cult classic by unraveling the consequences of living in a digital age that didn’t even fully exist yet.

Our Media, Our Selves

Though the book and its precursor, 1964’s Understanding Media, deal with a variety of ideas concerning the consumption of “media,” a crux of their narrative is this: Media, which is powered by ever-evolving technology, serves as an extension of our very selves. We created it to more adequately express ideas through sensory experiences. In return, interacting with these new means of expressing thought—through the printed word, TV, radio and today, the Internet (which McLuhan somehow predicted)—would actually rewire the way we think and relate to the world around us.

Because media was (and is) evolving so rapidly, McLuhan contended that the mediums of delivery themselves were far more important than the messages they delivered. Thus, even if the cover of the book had a typo, it didn’t really matter, because the content wasn’t the point in the first place.

Fast-forward 50 years, and most of our media—from traditional outlets like cable news and talk radio, to more recently emerging forums like social media and 24-hour sports networks—seem to be pushing a singular message, no matter what the content is: Strong opinions, confrontational ideas, loud voices—and, most of all, outrage—are what matters. The actual words themselves are secondary to their delivery:

Content is subject to volume. Context is meaningless without attitude. Anger trumps subtlety.

Anecdotes of Media Aggression

There’s no formal way to measure the overwhelming collective message of modern media, but there are anecdotal ones. On any given afternoon, TV talking heads can be heard aggressively arguing about a recent political decision, a 20-year-old college quarterback’s NFL-readiness, or the artistic merits of a new film. Turn on the same programs several months later, and the same talking heads will inevitably be having the same sorts of aggressive arguments, but the political issues, movies, or quarterbacks that they will be arguing about will be different ones altogether.

The same example could be used in social media, where fights breakout in Facebook threads over the latest headlines—headlines that are quickly forgotten when the news cycle finds something else to report on.

It’s not that the content or messages of this new era of media are completely irrelevant—it’s simply that they are often so temporal, that they are forgotten almost as quickly as they were deemed inflammatory.

The only thing that lasts is the delivery (the medium), making it the real content (the message) we end up hearing.

The Medium, the Message, and the Gospel

This is why, in modern media, the message of the Gospel is in danger of being lost on culture: The mediums we’ve created to communicate are slowly engulfing the messages Christians are called to share. The Gospel, which is ultimately a story of hope, peace, and grace, is being subjected to a medium that is sending a conflicting message.

Too many Christians have fallen into the trap of trying to conform their messages into mediums that are incompatible with the Gospel’s real content. When we constantly use outrage, culture war-speak, and combativeness in an attempt to get our message heard, people do end up hearing it, but the content is lost to the delivery.

Too many Christians have fallen into the trap of trying to conform their messages into mediums that are incompatible with the Gospel’s real content.

All technology is built to serve some sort of human need. And as McLuhan thought, it can actually be viewed as an extension of ourselves. Technology—and especially media, which is comprised of actual voices—is a megaphone that amplifies the most dominant parts of human nature. That’s why the era of modern media is so obsessed with arguing and outrage; they are real social issues that culture is grappling with.

Modern media gives us a glimpse into the state of human brokenness, and the things our culture is struggling with. We should use this as an opportunity for healing and redemption.

The problem is, as Christians, we shouldn’t be trying to change what we say (either consciously or unconsciously), in order to be more in line with human nature—we should be attempting to change human nature with what we say.

Inciting Outrage or Embodying Grace?

So, what does this look like? Understanding that an underlying message of modern media is that the things we say should incite outrage, when we encounter ideas that are opposed to our own, the reaction should be the opposite of that.

Instead of outrage, we should embody grace.

Instead of principle, we should embrace nuance.

Instead of looking for who to fight, boycott, or rally against, we should also be looking for opportunities to dialogue and to understand.

Though there are issues—that involve things like fighting injustice, representing important social causes, and defending the disenfranchised—that do call for outrage and action, if we don’t devote those attitudes only to moments that truly warrant them, we lessen their impact.

If a filmmaker takes creative liberties with a Bible story, a political party suggests legislation we don’t agree with, or a Christian pastor does or says something wrong, anger and hostility aren’t the right response. Grace, understanding, and patience should be our tone (medium) so that words (the message), even if they are strong, can be heard properly.

Meaningful Message in a Still, Small Medium

In 1 Kings 19, Elijah is sent to a mountain to wait on the presence of the Lord.

“A great and powerful wind tore the mountains apart and shattered the rocks before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind. After the wind there was an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake. After the earthquake came a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire. And after the fire came a gentle whisper.”

From there, God gave Elijah instructions on what to do next, but his message wasn’t just in His words to the prophet. The way God chose to speak was far more meaningful than anything He could have said to Elijah.

We live in an era of media where it’s easy to find voices that can tear through mountains, shatter rocks, shake the earth, and speak with fire. But the Lord isn’t always in the earthquake, the wind or the flames of outrage, and noise. The voice of the Lord is often heard a gentle whisper.

Sometimes that’s the loudest voice of all.

References