I hope you’ll forgive me, but I’m going to talk like a psychologist for a minute. I’m not always like this. Sometimes, I’m an actual human. I experience injustices like we all do, and I respond emotionally. When I talk about those experiences to my wife, children, or friends, I use terms like injustice, transgression, unforgiveness, resentment, bitterness, grudge, and vengeance imprecisely. But, when I speak as a psychologist, I distinguish among those terms because those fine distinctions can help people deal with injustices and feelings of resentment and bitterness.

“I Forgive You”

If a person says the words, “I forgive you,” instinctively you know that saying is not doing. The person could be setting you up to stab you in the back. So, when you hear those words, you immediately try to discern his or her internal state. This should suggest that forgiveness is something that happens inside a person’s skin—within their own inner psychology. The internal experiences that we call forgiveness can be manifest in relationships—and we might think that they should be manifest in relationships—but the saying should not be equated with forgiving.

Read Jesus’s words about forgiving: “Forgive us our debts as we also have forgiven our debtors … For if you forgive men when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive men their sins, your Father will not forgive your sins” (Matthew 6:12, 14-5; RSV). We often forgive people who harm or offend us—perhaps even seventy-seven times (or seventy times seven—i.e., every time). But we are dismayed when, the next time we see the person—or even think about the person—we still experience resentment, anger, anxiety, or bitterness, and perhaps even hold a grudge. In short, we feel unforgiveness. How can we forgive and still experience unforgiveness? Those seem incompatible. Yet, as we all know, somehow we often find ourselves snared in that paradox.

Decisional vs. Emotional Forgiveness

Actually, there seem to be two types of forgiveness, masked by the poverty of English language as one word. What I call decisional forgiveness is a sincere behavioral intention statement that says, “I have decided to treat this offender as a person of value, whom God loves—even if the person has rejected God.” Thus, we can choose to forgive and reorient our intentions toward the person. Yet, decisions can happen fast relative to the change of our emotions. A person can forgive (decisionally) and yet experience incomplete emotional forgiveness. Emotional forgiveness occurs through the emotional replacement of negative unforgiving emotions with positive other-oriented emotions like empathy, sympathy, compassion, or love for the offender. Replacing emotions is usually slow work.

A person who feels resentment is stirred up emotionally and thinks negatively toward the offender. But, when a person holds a grudge, usually the person is not just feeling negative toward the offender but either is plotting vengeance or payback, or is hoping (scarcely admitting that to himself or herself, or even to God) that bad tidings will befall the offender.

To Forgive Is Human

The ability to forgive is part of the imago Dei, which though corrupted by the fall is still part of common grace—just as rational thinking, self-control, and love are available (albeit imperfectly) to all humans. To forgive is human, yet redeemed humans have divine help that can lend a supernatural impetus to forgiving. Even though Scripture admonishes us to forgive, it does not instruct us how to do it, other than to rely on the power, grace, and mercy of God. The how-to of forgiveness is more a product of God’s general revelation. We can study the book of nature—and that is just what Christian psychologists try to do—to find out how we might better forgive.

Reaching Toward Forgiveness

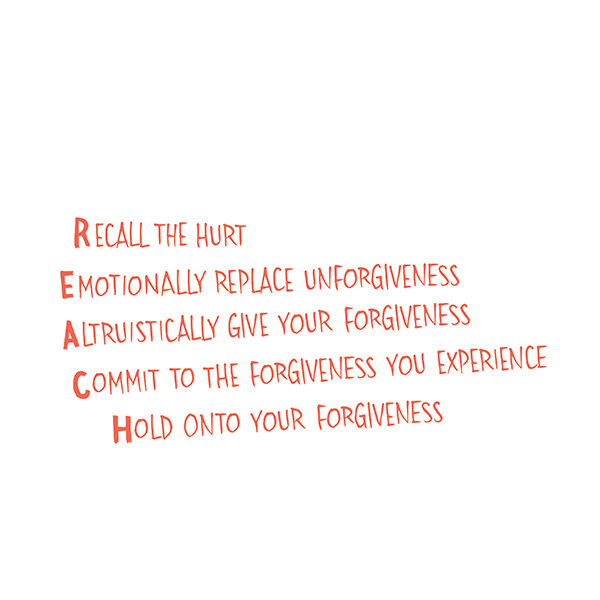

Forgiving is like building a pillar of concrete to support a structure. God supplies the “concrete” of lasting forgiveness. But Christians (and others) can supply wooden forms that shape the concrete into a pillar. The forms I teach are called the REACH Forgiveness method. REACH is an acrostic in which the five letters stand for five steps (see my Forgiving and Reconciling: Bridges to Wholeness and Hope, InterVarsity Press, 2003).

R stands for RECALL THE HURT—without blaming the offender or focusing on how much impairment one has suffered due to the offense. Rather, recall the hurt in a way that will allow EMOTIONAL REPLACEMENT—that’s the E. To emotionally replace the unforgiveness by positive other-oriented emotions, try to respond empathically, seeing things from the other person’s point of view. We have all offended and hurt others, yet we rarely think, Today, I’ll ruin someone’s life. Rather, we have good intentions, but they just go wrong in the enactment. The same is usually true of people who hurt us. Usually they started out thinking they could help, but it didn’t work out that way. Sometimes, of course, people do want to harm us, so then sympathy is more appropriate. We can feel sorry for a person who could get to the point of intending and enacting harm. Perhaps we can even muster up compassion or agape love for that person.

A is an ALTRUISTIC GIFT—not a purely self-interested gift—of forgiveness. It’s okay to want to forgive someone because holding the grudge is making us miserable. This is similar to wanting to know Jesus because it is a blessing to us. But we have found that, when people also want to forgive others to free the offender from blame—to loose a spiritual stranglehold they have on the offender—then (ironically) people are even better able to forgive than when their primary motive is their own freedom from grudges.

C stands for the COMMITMENT TO THE FORGIVENESS YOU EXPERIENCE. We coach people to make a statement—even if it is just to write a forgiveness statement that no one ever sees except the writer (e.g., “Today, I have forgiven x, for doing y to me”). These statements help to solidify forgiveness.

Another reason for performing some public expression of forgiveness is so we can H, HOLD ON TO FORGIVENESS when we doubt that we have forgiven. We do often doubt our own forgiveness. When we see the recently forgiven person, we often experience a rush of anxiety and anger. We doubt that we’ve forgiven because of those emotions. When you burn your hand on a stove, and later move your hand near the stove again, your body will react in both anxiety and anger. It’s not that you haven’t forgiven the stove. It’s that your body is responding exactly like God designed it—to use the emotions of anxiety and anger to warn you of potential harm. Often that anxiety and anger is interpreted by people who have forgiven an offender as the failure of complete forgiveness. But that is misleading. We must remember the fact of our forgiveness.

Now consider a special case of forgiving: forgiving oneself. This is a special case, since it often mixes being an offender (someone who has done a moral harm to another or hurt another, even unintentionally) and being a forgiver. We can also forgive ourselves by applying the REACH Forgiveness model to ourselves. Of course that self-forgiveness needs to occur after we have responsibly sought forgiveness from God and tried to repair the social damage done by amends making.

The Negative Effects of Unforgiveness

Holding grudges and self-condemnation are not good for us. And this has been shown by numerous psychological scientists who have produced and reviewed much research. The results are clear. Unforgiveness, resentment, holding grudges, and bitterness are not good for our physical health. Neither is self-condemnation. Those sources of stress put people at risk for cardiovascular diseases and events (like strokes, high blood pressure, heart attacks, etc.). These emotional states can also compromise and dysregulate (i.e., impair) our immune systems resulting in lack of ability to fight off physical diseases of many types. And they elevate cortisol. Cortisol is a stress hormone that is good in responding to immediate stressors, but when it stays high—as it does when we are chronically unforgiving or self-condemning—then it affects virtually every physical system in our bodies. This includes shrinking our brains, affecting digestion, sexual drive and performance, circulation, and immune system.

Resentment and chronic self-condemnation often lead to rumination—replaying those old memories over like B-grade zombie movies in the late-late show of the mind. Rumination is related to many types of psychological problems: depression, anxiety, stress-related problems, anger control, and psychosomatic problems.

And these negative emotional stressors wreak havoc on relationships. Blaming others and finding faults can set couples, families, friends, or work relationships into a downward spiral of blame and resentment. And frequent self-blame and complaint can tire relationship partners and exhaust caregivers.

Finally, holding onto bitterness, resentment, and self-condemnation have severe effects in our religious and spiritual lives. Anger at God has a distancing effect, sending people who have dwelt comfortably as Christians for years into times of angry or lonely wandering. In a recent meta-analysis, our team of researchers found religion to be highly related to forgiveness of others but not so much to forgiveness of self. Spirituality, understood as a personal, close relationship to God (and other things like nature, humans, or transcendent experiences), was more closely related to self-forgiveness but less to forgiving others. The Lord wants us to forgive and not to hold resentment, grudges, and unforgiveness—toward others or toward ourselves. And He is always there, eager to work in us when we ask for forgiveness, and the help to forgive others.