In 1534, Abbot Paul Bachmann published a virulent anti-Protestant booklet titled A Punch in the Mouth for the Lutheran Lying Wide-Gaping Throats. Not to be outdone, the Protestant court chaplain, Jerome Rauscher, responded with a treatise of his own, titled One Hundred Select, Great, Shameless, Fat, Well-Swilled, Stinking, Papistical Lies. Such was the tenor of theological discourse among many of the formative shapers of classical Protestantism and resurgent Roman Catholicism in the sixteenth century. Such rhetoric was brought from the Old World to the New. Fueled by local prejudice and nativist traditions, it continued to deepen the divide between the heirs of the Reformation debates.

The Shock of Common Ground

Imagine then the surprise—in some circles the shock—when on March 29, 1994, the statement “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium” was released in New York. Here, the old hostility between Catholics and Evangelicals was replaced by a new awareness of their common Christian identity—a shared life in Jesus Christ. The core affirmation of the first Evangelicals & Catholics Together (ECT) statement, and of the entire project, was this declaration:

“All who accept Christ as Lord and Savior are brothers and sisters in Christ. Evangelicals and Catholics are brothers and sisters in Christ. We have not chosen one another, just as we have not chosen Christ. He has chosen us, and He has chosen us to be his together.”

On the following day, the story of the new Evangelical and Catholic initiative was carried on the front page of The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and other newspapers across the country.

“The ECT participants were clear that they spoke from and to but not for their respective churches and denominations.”

Why Evangelicals & Catholics Together Was Different

The 1994 ECT statement, however, did represent something different.

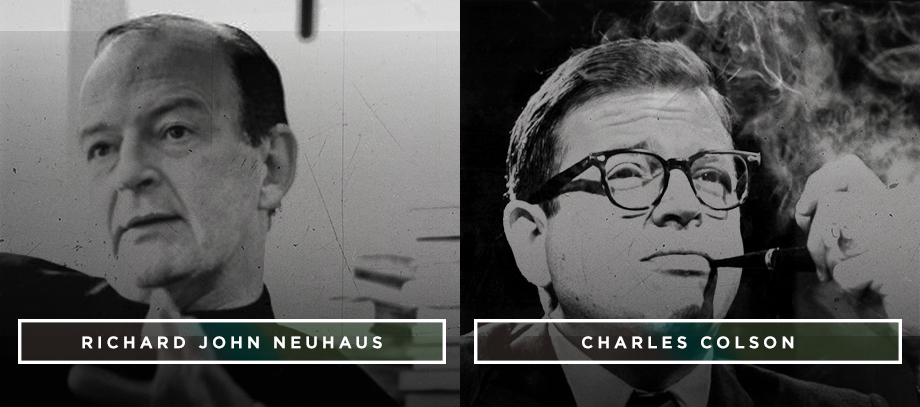

First, it was not an official, church-endorsed ecumenical dialogue but rather an ad hoc group of Catholic and Evangelical theologians brought together by Richard John Neuhaus and Charles W. Colson, Jr. The ECT participants were clear that they spoke from and to but not for their respective churches and denominations. The independent status of ECT made it more flexible and more responsive than traditional patterns of discourse.

Reacting to Evangelicals & Catholics Together

The reaction was immediate and explosive. While some saw this new effort as a hopeful sign, others, especially some conservative evangelicals on the right, were disturbed and distraught. Best-selling author Dave Hunt wrote of the ECT statement: “I believe the document represents the most devastating blow against the gospel in at least one thousand years.” For their part, many left-leaning progressives, both Catholic and Protestant, dismissed the statement as a publicity stunt tied to conservative politics.

My Take on the Evangelical & Catholic Unity

It seemed to me, however, that both of these narratives had badly misjudged the situation. When I was asked to write a lead editorial on ECT for Christianity Today, I described the new project in this way:

“Here is an ecumenism of the trenches born out of a common moral struggle to proclaim and embody the Gospel of Jesus Christ in a culture of disarray. This is not merely a case of politics making strange bedfellows. It is more like Abraham bargaining with God for the minimal number of righteous witnesses required to spare the sinful city of Sodom. For too long, ecumenism has been left to Left-leaning Catholics and mainline Protestants. For that reason alone, evangelicals should applaud this effort and rejoice in the progress it represents.”

Precedents for Christian Ecumenism

Of course, ECT did not come out of the blue. Ever since his 1957 crusade in New York City, Billy Graham had warmly welcomed Catholic participants in his evangelistic efforts. John Stott, an Anglican pastor with worldwide influence, had long engaged with Catholics in serious theological discussions on issues of mission and world evangelization. Further, an “ecumenism of the trenches” was already at work among many Evangelicals and Catholics in local communities who found themselves standing side by side in opposing abortion on demand and advocating for the traditional values of chastity, family, and community—all derived from deeply held religious convictions.

“There are many practical steps of spiritual ecumenism we can take together to show the world that we belong to Jesus Christ and are brothers and sisters together in him.”

Second, ECT represented a move beyond co-belligerency. While sharing many common moral concerns in what were then called the “culture wars,” the framers of ECT determined to address these issues precisely as believers in Jesus Christ. They took seriously the prayer of Jesus in John 17:21—“that they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me” (ESV).

Third, both Catholic and Evangelical participants recognized that the only unity worth having was unity in the truth. Rather than smudge over serious differences that still remain between the two traditions, it was decided to face these controverted issues with both candor and civility. Not all critics of ECT were persuaded that the project was successful in this regard, but the goal was clear: to practice an ecumenism of conviction, not an ecumenism of accommodation.