“Mother Teresa’s Crisis of Faith.”

That was the startling title of the Time magazine article in 2007 discussing the private spiritual struggles of Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Many were disconcerted when Mother Teresa’s private letters to her confessors were published after her death. There was shock and confusion that this iconic woman of faith would have experienced such spiritual desolation and doubt. For decades Mother Teresa had experienced an acute experience of separation from God. For example, here is one of her letters to her confessor (from the collection Come Be My Light, pp. 192-193):

September 1959

Part of My Confession Today

My own Jesus,

They say people in hell suffer eternal pain because of the loss of God—they would go through all that suffering if they had just a little hope of possessing God.—In my soul I feel just that terrible pain of loss—of God not wanting me—of God not being God—of God not really existing (Jesus, please forgive my blasphemies—I have been told to write everything). That darkness surrounds me on all sides—I can’t lift my soul to God…

In my heart there is no faith—no love—no trust—there is so much pain—the pain of longing, the pain of not being wanted.—I want God with all the powers of my soul—and yet there between us—there is terrible separation.—I don’t pray any longer.

© 1986 Túrelio (Wikimedia-Commons) / Lizenz: Creative Commons CC-BY-SA-2.0 de

What I find interesting in the public response to the spiritual struggles of Mother Teresa is just how surprised people were. Specifically, that surprise seems to have been generated by an implicit assumption that faith and doubt are antithetical, existing at two extreme ends of a continuum. On the one side is faith and on the other side is doubt. And as one increases the other decreases. The more faith the less doubt. And visa versa.

And yet, as the experience of Mother Teresa illustrates, this simplistic model breaks down when we consider the lived experience of faith. As the psalms of lament and complaint amply illustrate, faith is often accompanied by acute experiences of God’s silence, abandonment, and antagonism. The faith experience is often filled with questions and accusations of God.

“It’s surprising how ill-equipped many evangelical communities are in using the psalms in worship and spiritual formation.”

Psychologically speaking, this sort of relational distress makes sense. Psychologists using relational models (e.g., object-relations, attachment theory) to understand our experience of being “in relationship” with God have long noted how our emotional experiences with God are, in the biblical witness, understood in the idiom of human relationality and attachment. Specifically, in the Bible relationship with God is often described as a parental, romantic, or peer attachment:

God speaking to his people: “As a mother comforts her child so I will comfort you.” (Isaiah 66:13)

Jesus teaching his followers how to address God in prayer: “Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name.” (Matthew 6:9)

A description of God’s love for his people: “As a bridegroom rejoices over his bride, so will your God rejoice over you.” (Isaiah 62:5)

A description of God’s relationship with his people: “For your Maker is your husband—the Lord Almighty is his name.” (Isaiah 54:5)

A New Testament description of Abraham’s relationship with God: “And the scripture was fulfilled that says, ‘Abraham believed God, and it was credited to him as righteousness, and he was called God’s friend.” (James 2.23)

Job describing his prior relationship with God: “Oh, for the days when I was in my prime, when God’s intimate friendship blessed my house…” (Job 29:4)

And as we all know, these relationships—parental, romantic, friendship—are often filled with conflict and relational strain.

Thus, why would our relationship with God be any different?

And yet, it seems that in many locations within Christianity there is a great hesitancy to give voice to any negativity regarding our relationship with God. Again, the reason for this seems to be the assumption described above, that any distress, complaint or negativity in the God-relationship is symptomatic of a lack or loss of faith. Thus the voice of complaint—the hot cry of lament heard in the psalms—is silenced within the faith community. The assumption behind this sort of spiritual formation is that giving voice to complaint and questioning would undermine faith.

“In failing to give voice to lament, as we see with the Psalms, we’ve given our faith communities an unrealistic expectation of what it feels like to be in relationship with God.”

But is that so? Might avoidance of complaint be, rather, symptomatic of a lack of faith? Consider this assessment from Walter Brueggemann about why many evangelicals don’t use the lament psalms as a part of their worship (The Message of the Psalms, pp. 51-52):

It is a curious fact that the church has, by and large, continued to sing songs of orientation in a world increasingly experienced as disoriented… It is my judgment that this action of the church is less an evangelical defiance guided by faith, and much more a frightened, numb denial and deception that does not want to acknowledge or experience the disorientation of life… Such a denial and cover-up, which I take it to be, is an odd inclination for passionate Bible users, given the larger number of psalms that are songs of lament, protest, and complaint about an incoherence that is experienced in the world… I believe that serious religious use of the lament psalms has been minimal because we have believed that faith does not mean to acknowledge and embrace negativity.

We see here Brueggemann criticizing the implicit assumption that faith and negativity cannot exist within the same relational space, the assumption many are working with that faith and negativity are antithetical experiences, two extreme ends on a continuum. But Brueggemann goes on to suggest that the witness of the psalms clearly indicates that faith and negativity, as seen in the life of Mother Teresa, do mix. In fact, according to Brueggemann the expression of complaint within the faith community, rather than it’s silencing, may be the strongest indicator of faith. Brueggemann:

We have thought that acknowledgement of negativity was somehow an act of unfaith, as though the very speech about it conceded too much about God’s “loss of control”… The point to be urged here is this: The use of these “psalms of darkness” may be judged by the world to be acts of unfaith and failure, but for the trusting community, their use is an act of bold faith.

In my own research I’ve described this mixture of faith and complaint as the “Winter Christian” experience. And as I’ve described this experience to various faith communities I’m often asked about how the community might help give voice to the experiences of lament, doubt, dryness, complaint, and questioning that are the natural rhythms of any relationship, in this case our love relationship with God.

My response to these faith communities has been consistent: Use the psalms.

It’s a simple and obvious recommendation. But it’s surprising how ill-equipped many evangelical communities are in using the psalms in worship and spiritual formation.

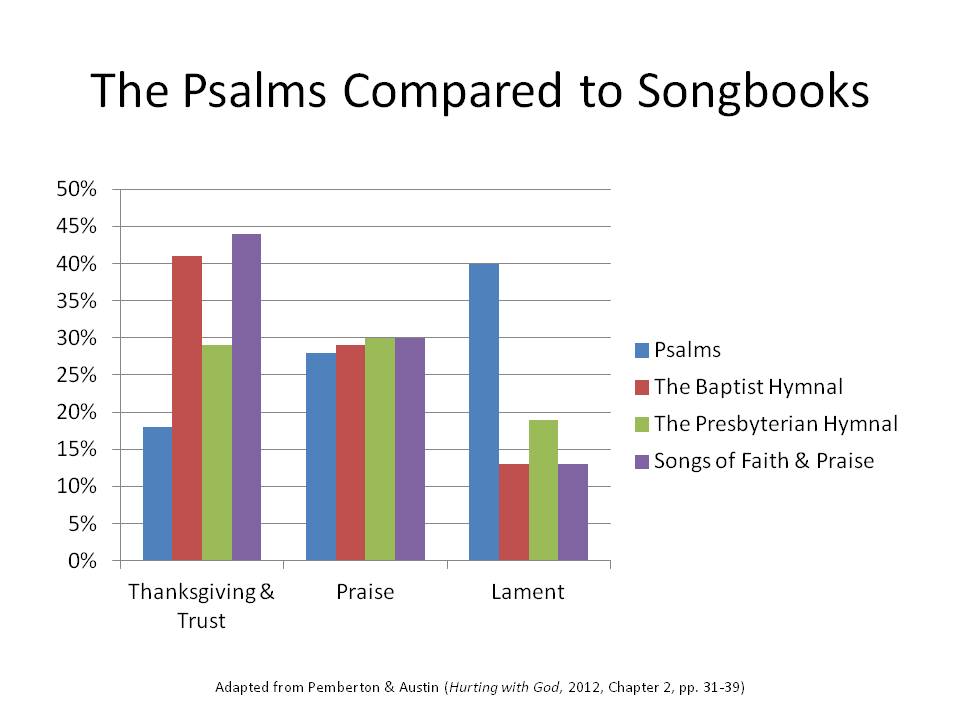

Consider the analysis done by my ACU colleague Glenn Pemberton in his book Hurting with God: Learning to Lament with the Psalms. Glenn inventoried the content of the Psalms and then compared that with the content of three songbooks—Songs of Faith and Praise, The Baptist Hymnal, and The Presbyterian Hymnal.

According to Glenn’s coding system the three largest categories of songs, for the Psalms and the three songbooks, were songs of Trust and Thanksgiving, songs of Praise, and songs of Lament. Using these categories Glenn calculating the percentage of the songs in each of the categories. (There were more than three categories. I’m just focusing on the largest three.) Comparing the content of the Psalms with the songbooks, the following chart represents what Glenn found:

Notice anything interesting?

Notice that 40% of the Psalms can be classified as lament. In contrast, the three songbooks don’t even crack 20%. And two of them don’t crack 15%.

Of course these are hymnbooks, but I doubt that standard praise song content in many evangelical churches would fare any better by comparison.

The point is drawing your attention to this comparison is that many churches are ill-equipped to give voice to the Winter Christian experience. Our worship, to make this point sharp, isn’t biblical enough. And in failing to give voice to lament, as we see with the Psalms, we’ve given our faith communities an unrealistic expectation of what it feels like to be in relationship with God.

And from a spiritual formation perspective this is problematic for two inter-related reasons:

1. When we fail to give voice to complaint, doubt and lament these experiences become internalized and privatized. We begin to feel alone and isolated in our spiritual struggles.

2. When we fail to give voice to the Winter Christian experience we begin to pathologizedoubt and lament. We send the message that lament and complaint is a spiritual failure, even a sin.

This creates a toxic mix. When spiritual struggles are privatized and pathologized we experience increasing alienation and disengagement within the faith community. We feel that we don’t belong, that there is something wrong with us. And when this feeling of alienation grows strong enough we walk away from both the faith community and faith itself.

So let us sing the psalms, as an act of bold faith. Let us praise and lament.

That is what loving God feels like.